The dramatic allure of other people’s awful experiences.

We can experience effects from traumatic events remotely, but without the nuance of when we’re directly affected.

Whenever something truly horrible happens, our human instinct — perhaps even our animal instinct—is to sense the significance. Tragic events tear us away from the mundane, the familiar, and the routine, and in the harsh light they shine on everything around us, they can remind us of what matters.

So it follows that major tragic events become major news stories, dominating the airwaves and bandwidth. Of course people want to learn about them and discuss them: they want to know the details, what happened, who was affected, how it happened, and, to the extent anyone can answer it, why it happened.

But between the seemingly saturated news coverage and the immediacy of interacting on social media, the experience of someone even halfway around the world from an event can go well beyond talking about it. People can immerse themselves in it.

And not necessarily in objectively useful ways. Twitter, for example, is an amazing tool and resource, but in times of crisis, it’s surely a mixed bag. The amount of misinformation and disinformation and horrific hot takes that can be spread in a matter of minutes — it’s just staggering.

FOMO vs. Compulsion To Contribute

At the same time a force beckons us to weigh in. It’s reminiscent of FOMO, the Fear Of Missing Out, but maybe it’s the flip side: some sort of need to be part of the action. Let’s call it Compulsion To Contribute. I’ve also written about Fear Of Not Sharing, but that has more to do with the sense that an experience you’ve actually lived isn’t as dimensional for you without sharing it online. Instead, this compulsion tells you that the thing you’re reading about online isn’t as real unless you try to find a way to be part of it.

I don’t know why people are drawn to drama, but it seems undeniable that they are. I’m reminded of this phenomenon I’ve observed repeatedly about people glomming on to the legacy of the deceased when someone dies. All of a sudden people claim to have been the dead person’s best friend. Maybe people romanticize tragedy, somehow.

(That thought in turn reminds me somewhat of reading about songwriters like Tom Petty and Elvis Costello who admitted to sometimes sabotaging romantic relationships so they would have some well of authentic emotion to write about.)

But maybe there is something universal about the way a tragedy that didn’t happen to us gives us a glimpse at the shadow side of life’s experiences without actually having to, y’know, experience it.

The Dimensionality of Being There

It’s a shallow way to feel the shadow side, though. And as someone who has experienced life-changing tragedy from as close-up as it gets, I know that the glimpses one gets from afar don’t feel like the real thing and they sure don’t tell the whole story.

They leave out the part, for example, about how resilient people can suddenly find themselves being. You can’t get that by proxy; you can only really bask in that resilience if you’re genuinely close to the tragedy and you would otherwise be expected to crater under the strain. For example this morning I saw media interviews with people in London last night who talked about how these were fundamentalist attacks on the values of their Western lifestyles but they insisted that they wouldn’t change their lifestyle out of fear. The thing is, if you’re watching the horror unfold from half a world away, especially through the clickbait-iest of news stories and the viral-est of retweeted tweets, you can only experience the abject fear of the event. When you’re up close and in it, you just might feel that part about the defiance of fear, too, and it’s that part that offers some slight counterbalance to the awfulness of the experience that can help a survivor survive.

There’s a nuanced dimensionality to any lived experience that becomes less perceptible from farther away. Just like a pointillist painting, from a distance maybe it blurs into an integrated image. But up close there’s a whole lot going on.

Remote Tragedy, Terror, and the Meaning of Place

It’s also interesting to consider proximity in the experience of remote tragedy, such as terror attacks, as they relate to the experience of place. I’ve written about digital identities and how we conduct ourselves online and I’ve written extensively about the meaning of place, but terror attacks in general tend to be very place-specific.

In other words, the attack can be assumed to be at least partially motivated by the meaning of the place. The hijackers that flew planes into the twin World Trade Center towers on 9/11 didn’t just choose them, presumably, because they were merely tall buildings; they chose them because of what they represented: capitalism, ambition, and other characteristically American and Western ideals. And Americans, by and large, but especially New Yorkers, responded by saying they were going to go right on being characteristically American. Maybe they didn’t say it exactly like that, but that was the gist of what people meant when they implored: “don’t let the terrorists win” and went right on going out to dinner and to movies and trying to live life as if it felt normal.

The experience of tragedy within the place where it occurs, which is intrinsically linked to the tragedy, and outside the place where it occurs is almost certainly different. Even watching reports of a natural disaster from outside the affected area can have tremendously different significance from being nearby—knowing the landmarks, and understanding at an intuitive level the cultural, economic, and social impacts of the catastrophe.

Self-Removal for Self Preservation

Maybe it’s human nature to be lookie-loos gaping at a global car crash on the information superhighway, but it’s not without harm, even to ourselves.

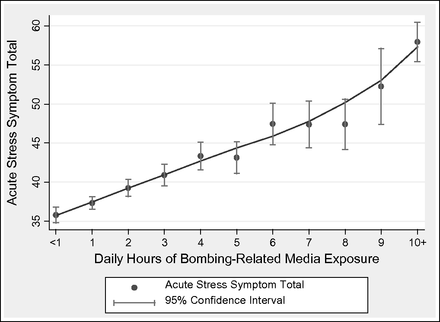

If you absorb yourself in drama remotely, you get all the stress of the event without the dimensionality of experiencing and surviving it. For example, according to a study published in the journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America):

those who spent more than six hours a day watching media coverage of the April 15 Boston Marathon bombing and its aftermath suffered more powerful stress reactions than did people who were directly involved but watched less news coverage of the events.

— http://www.latimes.com/science/sciencenow/la-sci-media-coverage-trauma-stress-20131209-story.html

But once you’ve actually been through something awful, there are opportunities to feel stronger, more resilient, more connected to the community around you, for having survived it. People who aren’t there who immerse themselves in the details and drama of the story may actually endure more suffering without any of the benefit of feeling stronger for having survived it.

So personally, at times like after last night’s attack on the London Bridge and the Borough Market, I try to practice some self-removal. I try to take myself out of it. Not just in the sense that I may not participate in the immediate social shares about the event if I have nothing urgent to contribute, but at a more philosophical level: as I ponder the experience of the event, I try to take my self out of it and immerse myself fully in compassion and empathy for those who were there.

After all, I wasn’t there; it isn’t about me. And this is both a matter of survival and an opportunity to be grateful. It’s all too easy to insert yourself into a social media narrative around something happening somewhere else in the world that in actuality affects you very little.

(As an aside: it may seem like the opposite of self-removal for me to have written this post, but for what it’s worth, I wrote this not to weigh in on the attacks but to attempt to connect some research I’d collected about tragedy and experience with some of my own thinking. As someone whose work explores the overlap of meaningful human experience and digital culture, I wanted to examine what it means for people to experience tragedy remotely and how sharing digital content contributes to it. I’m writing at a level of abstraction removed from the specifics of the attacks, not commenting on the incident itself. I don’t have any hot takes.)

Comfort In

It comes down, in some ways, to Susan Silk and Barry Goldman’s “Ring Theory” about levels of significance of grief. In their model, the person who is the most aggrieved is at the center, and everyone else who is less directly affected should offer only comfort towards anyone further in, but if they want to complain, they can only do so outwards to people less affected.

“Here are the rules. The person in the center ring can say anything she wants to anyone, anywhere. She can kvetch and complain and whine and moan and curse the heavens and say, “Life is unfair” and “Why me?” That’s the one payoff for being in the center ring.”

— http://articles.latimes.com/2013/apr/07/opinion/la-oe-0407-silk-ring-theory-20130407

It’s Not About You, Or Me, And Thank Goodness

I don’t know why we obsess over others’ tragedies. Are we trying to share in each other’s experiences, trying to lessen each other’s burdens through sharing them? Are we trying to live vicariously dramatic lives, trying to have a bit of the awful glory of attention for ourselves, or what? What drives us?

It’s certainly not that I think if you weren’t there, you shouldn’t care. And I don’t think we should necessarily abstain from tweeting or posting to Facebook or whatever we might be inclined to do in a tragedy.

I do think, though, that before we do that, we should think about two things: first, whether we may be able to offer genuine comfort to people more directly affected by the tragedy by either saying or doing something different than we are first inclined to say or do, or by perhaps saying nothing; and second, whether we may be better off ourselves by immersing ourselves less in TV news loops and endless online rehashing of the details.

It probably isn’t about you or me. Not this time. But if it ever is, I assure you, we will appreciate people treating us with the respect and compassion we deserve in that moment.

Thank you for reading. Please “clap” if you found this piece interesting or meaningful. And please feel free to share widely.

Kate O’Neill, founder of KO Insights, is an author and speaker focused on making technology better for business and for humans. Her work explores digital transformation from a human-centric approach, as well as how data and technology are shaping the future of meaningful human experiences. Her latest books are Tech Humanist: How You Can Make Technology Better for Business and Better for Humans (2018) and Pixels and Place: Connecting Human Experience Across Digital and Physical Spaces (2016).